For the second time this year, the Supreme Court could hear oral arguments on a relatively untested area of constitutional law as it relates to former President Donald Trump and set a landmark precedent that could affect the 2024 presidential race.

Chief Justice John Roberts showed interest on Feb. 13 in reviewing former President Donald Trump’s request the prior day to halt a ruling against his presidential immunity claims in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit.

Special counsel Jack Smith responded on Feb. 14, telling the court it should deny President Trump’s request.

Earlier this month, three D.C. Circuit judges rejected President Trump’s claim that the doctrine of presidential immunity shielded him from Mr. Smith’s prosecution related to the events of Jan. 6, 2021.

Mr. Smith had asked the Supreme Court to fast-track President Trump’s immunity appeal, but in December 2023, it declined, letting the D.C. Circuit tackle the issue first.

The appeals court set up a tight timeline for President Trump to request the Supreme Court’s review before the district court continued its recently forestalled pre-trial proceedings. Initially scheduled for March 4, that trial is one of many that could interfere with President Trump’s campaign schedule and raise questions about the judiciary’s relationship with American democracy.

The presidential immunity issue also raises questions about how presidents may contest election results, the threats they could face from future administrations, and whether the Constitution’s separation of powers precludes courts from weighing in on certain presidential actions before Congress.

As President Trump noted to the Supreme Court, the case presents a novel question that could have enormous consequences for future executives.

The “claim that presidents have absolute immunity from criminal prosecution for their official acts presents a novel, complex, and momentous question that warrants careful consideration on appeal,” President Trump’s Feb. 12 brief to the Supreme Court said.

The ‘Outer Perimeter’

Presidential immunity from judicial review has been broadly upheld since Marbury v. Madison in 1803. Although the case established judicial review over executive branch decisions, Chief Justice John Marshall’s majority opinion criticized the idea that courts had jurisdiction over a president’s discretion.

“The province of the court is, solely, to decide on the rights of individuals, not to inquire how the executive, or executive officers, perform duties in which they have a discretion,” he wrote.

Presidential immunity’s contours, however, are blurry in part because the Constitution doesn’t explicitly define the doctrine. Instead, a series of court decisions and DOJ opinions have interpreted the Constitution to provide a general outline of how presidents should be shielded from prosecution.

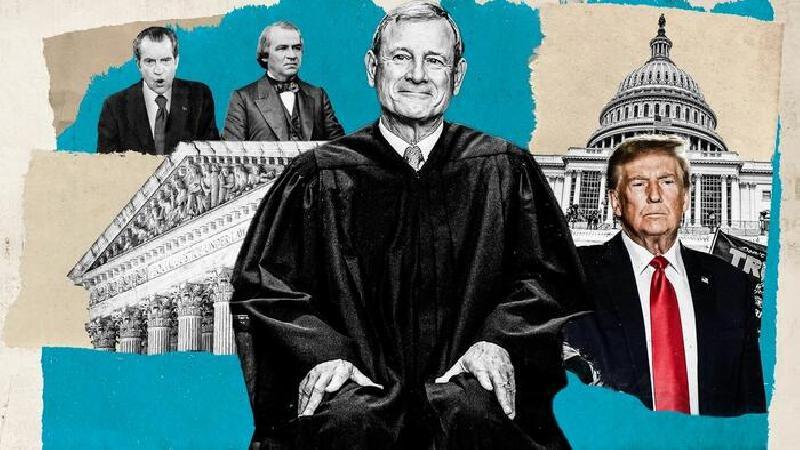

President Trump’s brief cites two Supreme Court decisions—Mississippi v. Johnson and Nixon v. Fitzgerald—in which the judiciary used suits against former Presidents Andrew Johnson and Richard Nixon to define the limitations of judges in reviewing presidential actions.

In Mississippi v. Johnson, the court denied Mississippi’s request to prevent President Johnson from enforcing the Reconstruction Acts because, the court said, it had “no jurisdiction of a bill to enjoin the President in the performance of his official duties.”

The court also distinguished between ministerial duties, or a straightforward adherence to the law, and discretionary duties, which involve the president’s exercising his judgment as to how he should carry out responsibilities assigned by Congress. Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase’s majority opinion quoted Chief Justice Marshall in describing meddling in the executive’s “prerogatives” as “an extravagance, so absurd and excessive.”

Former Justice Lewis Powell went further in Nixon v. Fitzgerald by ruling that President Nixon had “absolute immunity” from civil liability related to “official acts” within the “outer perimeter” of his authority. How far that “outer perimeter” extends is the subject of debate. In this case, the Court ruled that that authority included dismissing a federal employee—A. Ernest Fitzgerald—who alleged unlawful retaliation for testimony he gave to Congress.

That decision left open the question of whether a president could face criminal charges, but it distinguished between criminal and civil matters.

The court said: “When judicial action is needed to serve broad public interests—as when the Court acts not in derogation of the separation of powers, but to maintain their proper balance … or to vindicate the public interest in an ongoing criminal prosecution … the exercise of jurisdiction has been held warranted.”

Even that distinction, however, is under question with President Trump’s response to the 2020 election. The D.C. Circuit ruled in December 2023 that he wasn’t immune from civil lawsuits related to Jan. 6 because he had acted in his capacity as a presidential candidate, not exercising his official duties as president.

In his criminal case, President Trump maintained that the DOJ was attempting to charge him for actions that fell within his “official” duties and that he therefore should receive immunity. President Trump’s attorney, D. John Sauer, attempted to convince the appellate court in January that the Constitution requires Congress to impeach and try a president for his official acts before he can be charged criminally in a court of law.

Because the Senate already acquitted President Trump, Mr. Sauer argued, prosecuting him would violate the principle of double jeopardy.

The appellate judges rejected those arguments and ruled: “For the purpose of this criminal case, former President Trump has become citizen Trump, with all of the defenses of any other criminal defendant. But any executive immunity that may have protected him while he served as President no longer protects him against this prosecution.”

According to the judges, President Trump had misread Marbury v. Madison and the Constitution’s separation of powers. “Properly understood, the separation of powers doctrine may immunize lawful discretionary acts but does not bar the federal criminal prosecution of a former President for every official act,” the court said.

In legal memos from 1973 and 2000, the Justice Department opposed indicting or criminally prosecuting a sitting president. Former special counsel Robert Mueller, who investigated allegations of Russian collusion by then-candidate Trump’s campaign, cited the 1973 memo as a reason why he couldn’t indict President Trump. Those memos, however, don’t bind the Supreme Court in its determination of whether he can be indicted as a former president.

Potential Supreme Court Rulings

The Supreme Court generally has an array of options available when it decides cases, making its decision often difficult to predict.

First, the justices will need to decide whether or not to grant President Trump’s requested stay, which could effectively prevent the district court trial from proceeding.

In its Feb. 6 decision, the appellate court said it would withhold its mandate for the district court proceedings to continue if President Trump notified the court by Feb. 12 that he filed an appeal with the Supreme Court, which he did.

Appellants generally can seek en banc review, or a separate hearing with the entire circuit, if they lose their initial appeal. The three appellate judges said President Trump’s request for an en banc hearing wouldn’t delay the district court’s proceedings unless his request was granted by the circuit.

via magatribute