Everyone loves a good apocalypse, and in 2022, there’s an end-times for everyone.

Some apocalypses are fictional—great for corporate lobbying and political ambition. Others are overplayed as a “get rich quick” scheme that vanishes without explanation.

But the real apocalypses, the ones that pose a genuine threat to civilisation, rarely make it to print. After all, there’s a difference between fear and terror, and no sensible politician wants to start a panic.

Societies built on technology become vulnerable to its flaws in the same way desert empires fear cloudless skies.

At the rate human civilisation is evolving, a true digital catastrophe would likely cause a Year Zero event, an epoch defined by digital darkness.

If important data was lost—assets wiped and identity data destroyed—there would be a resetting of civilisation. However, it would be foolish to imagine human beings can recover as quickly as a computer operating system.

Humanity has come close to digital calamity before, but not since crawling into the womb of Silicon Valley.

The digital revolution happened within a single lifetime, and we find ourselves in the difficult position of wanting to embrace technology without ending up imprisoned by it.

While we are busy avoiding virtual mouse traps laid by the government, we must take care to keep redundancies within society to protect against inevitable periods of digital failure. After all, one week without power is enough to send advanced cities into ruin.

The next digital apocalypse will not be stopped by teams of sweaty programmers, red-eyed and shaking in the din of the world’s server rooms.

The Y2K Bug

Some of us are old enough to remember when an innocent mistake from the dawning age of computers created panic in 1999.

The “Y2K bug” was a simple flaw in the handling of dates during calculations when four-digit dates were truncated into two digits to save space. This was fine from 1960 to 1999, but as the year 2000 approached, programmers had to stop procrastinating and patch the error which threatened the security of everything from banking to nuclear power plants, airliners, factory machinery, and the commercial world, while satellite systems and GPS posed a physical risk to safety.

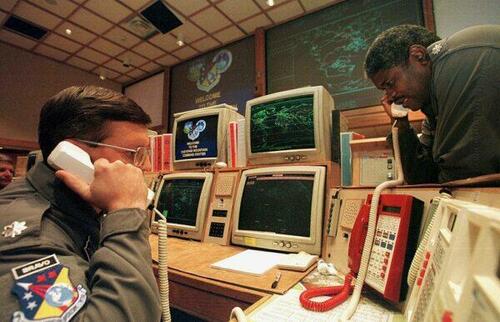

Missile Commanders Lt. (L) and Lt. Col. Ken Reed confirm a launch warning over the phone during a practice drill at the North America Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) Cheyenne Mountain Complex in Colorado Springs, Colo., Nov. 9, 1999. (Mark Leffingwell/AFP via Getty Images)

The tech industry was all at sea during this time, fixing micro-cracks on a listing cruise liner. It was an odd apocalypse because if you were not a programmer, there was nothing you could do.

Unlike the “bend the knee” mantra of climate change, the December of 1999 ended with an almost Norse fatalism culminating in a massive party beneath the Sydney Harbour Bridge (at least in Australia).

The crowd was covered in glitter, neon glow sticks, and outrageous heart-antenna headbands—three sheets to the wind on champagne. Most expected their city to go black and for the world’s computers to cough and die.

They didn’t. Those programmers worked to the last stroke of midnight. The bridge erupted in colourful plumes of gunpowder. The apocalypse was so uneventful that 22 years on, there are articles wrongly dismissing the danger.

No one had anything to gain from the Y2K bug. It was a pest ruthlessly exterminated by every government. (Shhhh. Let’s not talk about the year 2038 problem).

The Next Digital Apocalypse May Lead to a ‘Great Reset’

If the next long-prophesied digital apocalypse proves advantageous for those hoping to “reset” the global economy, our data may be sacrificed to serve “the greater good.”

A catastrophic loss of data would require a “fair system” of recovery—a “re-distribution” of assets, like a toddler knocking over a Monopoly board only for the parents to “fairly” put the houses back on all the squares regardless of who bought them. Those in dispute are gifted to the bank. Depending on a nation’s debt, loan-forgiveness in exchange for property acquisition is likely.

A digital apocalypse of this scale would probably arise from physical damage to the world’s largest server farms rather than cyber warfare. It’s much more effective to flatten a building, cut a cable, or even sustain a natural occurrence such as the Carrington Event of 1859.

An unstable energy grid, while not permanently destructive, would induce periods of digital interference that may alter our dependence on high-tech solutions in our economy.

In the real world, retailers are quick to switch to cash after an hour of blackouts.

If the tech community is honest with the public, the next digital apocalypse will not be malicious attacks from our friends in North Korea. It won’t be a gremlin from the 70s chewing on the cords nor a Nigerian Prince with a recently deceased relative.

Our apocalypse will be conducted in the halls of Parliament, designed by lobbyists and politicians who are rapidly transforming the digital world into an intangible prison block.

The loss of citizen control over the digital realm, replaced by the desires of the state, is an apocalypse humanity can never recover from. It would be the end of the free market Eden that forged our greatest technological achievements.

In its place, we will find an arms race of control that extends into our thoughts and beneath our skin.