The prospects for additional Russian sanctions depend mainly on how the war in Ukraine unfolds, but as Goldman writes in a note this afternoon, at this point further escalation of sanctions seems likely especially with Congress set to vote on a Russian oil import ban.

If the Biden Administration deems additional steps necessary, Goldman believes that we could expect one or more of the following actions:

- blocking more Russian individuals and related companies,

- blocking additional banks or restricting their ability to clear dollar transactions,

- eliminating exceptions to sanctions for energy transactions,

- banning imports of Russian energy,

- raising tariffs on imports from Russia,

- denying Russia most-favored nation (MFN) status.

- additional direct sanctions on Russian energy, perhaps starting with a ban on purchasing Russian oil.

Some more details on all of these:

- Sanctions on additional individuals and companies: The US has fully blocked several individuals and Russian banks, while imposing lower-level sanctions—primarily debt/equity restrictions and trading restrictions—on several other Russian companies. It appears likely that the Treasury will announce full blocking of additional individuals. This could also apply to companies outside of the banking sector, either by virtue of their relationship to sanctioned individuals or separately.

- Blocking additional banks: Thus far, the US has fully blocked 25% of Russian banks by assets. Including correspondent account restrictions on Sberbank takes the share to 57%. If the US deems additional sanctions to be necessary, the Treasury could expand the list of banks subject to sanctions. The odds of doing so might also increase if it becomes clear that other smaller non-sanctioned institutions have supplanted the originally sanctioned banks.

- Tariffs: The US and other countries appear likely to move to revoke Russia’s most-favored nation (MFN) status, which nearly every country qualifies for (the US excludes only two countries from this designation: Cuba and North Korea). This would raise the level of tariffs from the current applied rate—around 3% on average—to more than 10 times that. As the US imported only $29.7bn from Russia in 2021, subjecting US imports from Russia to non-MFN tariff rates would have a negligible effect. However, the US would be unlikely to act alone, particularly as the most likely means of tariff increase is for the World Trade Organization (WTO) to rescind Russia’s membership (this would likely take an affirmative vote of ¾ of WTO members; just over ¾ of WTO membership supported the UN resolution censuring Russia, though this does not guarantee they would vote the same way with regard to WTO membership).

- Eliminating general licenses for energy transactions: The Treasury has issued limited and time-specific “general licenses” for US entities to transact with some Russian sanctions targets when those transactions involve energy, agriculture, and medical goods. As shown on the left of Exhibit 1, energy exports account for 13% of Russian GDP, and while energy exports to the US are a very small share of this, rescinding the general license for energy could make it more difficult for firms in third countries to transact with Russian energy firms.

- Imposing a direct ban on the import of Russian energy products: There is growing political support in Congress for a ban on importing Russian crude and if put to a vote, it would likely pass with fairly broad support. While the White House has expressed reluctance to ban US purchases of Russian energy, legislative activity is apt to shine a political spotlight on the issue and increase the odds that the Biden Administration takes this step (over the weekend, Sec. of State Anthony Blinken said that “we are now talking to our European partners and allies to look in a coordinated way at the prospect of banning the import of Russian oil while making sure that there is still an appropriate supply of oil in world markets”). While the situation is fluid, it is more likely than not that the US will ban Russian oil imports, either via an administrative decision or legislation. If the ban is put in place, expect the White House to simultaneously announce offsetting measures, potentially including additional releases from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) and measures to encourage domestic production. We are skeptical that Congress would suspend the federal gasoline tax to offset a rise in prices, though this cannot be ruled out.

- Overall ban on trade, investment, and financing: In 1995, the US prohibited US firms from exporting to, importing from, or investing in Iran, with very few exceptions. This followed a ban imposed earlier that year on investment in the Iranian energy sector. In 1997, the ban expanded to also prohibit export of US goods to third countries if those exports were expected to be re-exported to Russia. Neither the EU nor other allies followed the US lead on an across-the-board investment ban on Iran. In theory, if the US deems it necessary to broaden sanctions to cover most of the Russian economy, this could serve as a precedent. Russia-US foreign direct investment is quite small, but FDI from the EU into Russia is substantial (Exhibit 1, right).

Perhaps just as importantly, at this time, the US has not indicated whether it will use secondary sanctions to enforce compliance with US sanctions in third countries that have not imposed their own Russia-related sanctions (such as China), but doing so would also increase the severity of any of the sanctions the US has or will impose.

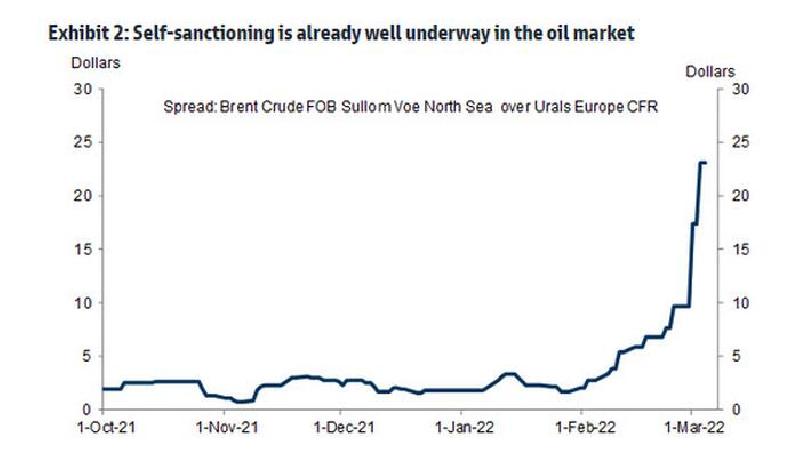

According to Goldman, in the near-term, the economic effects of additional US or allied sanctions would likely be mitigated by the fact that prices in some markets like oil already appear to be building in a high probability that further sanctions will be imposed, while many firms are voluntarily curtailing business with Russia by “self-sanctioning.” That said, near-term sanctions decisions will still be important as there will be a high bar to reversing them once they are in place.

More on that point: while expectations of further restrictions appear to be running ahead of actual policy announcements, the actual legal restrictions are likely to eventually become the binding constraint. While there is no precedent for sanctions with this scope on an economy the size of Russia’s, two other precedents suggest that whatever sanctions the US and allies impose could be in place for a while. First, the sanctions of similar or greater severity that the US has imposed on smaller economies like Iran or North Korea have for the most part remained in place since they were imposed, indicating a very high bar for reversing them. Second, the less severe measures the US has imposed on a larger economy—tariffs and export controls related to China—were thought to be temporary but have proved to be durable even with a change in presidential administrations.

The risks to supply chains and energy supply from the war in Ukraine has also increases the odds for domestic measures in those areas. Goldman had already expected Congress to approve semiconductor manufacturing and supply-chain-related incentives, and this looks incrementally more likely now. The $550bn/10yrs energy and climate provisions in the long-stalled Build Back Better (BBB) legislation are also likely to get renewed attention in Congress. And while Goldman does not see enactment of a scaled-back BBB as the base case at this point, the bank thinks the odds have increased considerably as a result of recent events.

via zerohedge